Artificial intelligence as primitive accumulation: enclosure, extraction ...

AI systems are imposing escalating calls on the key resources of energy, water, land, and minerals and on the hidden labor, often located ‘offshore’, required to build and service them. These demands are the latest episodes in the long history of capitalist accumulation and exploitation organized around enclosure and extraction. This paper suggests that we can usefully begin tracing continuities by revisiting Marx’s analysis of primitive accumulation and David Harvey’s notion of accumulation by dispossession.

Marx identified the enclosure of the English commons and the labor and resources delivered by colonial exploitation as the essential foundations of Britain’s leading role in establishing industrial capitalism. The same basic processes have fueled the unprecedented concentration of control over digital media and AI now exercised in the West by a handful of US corporations. The neoliberal pursuit of marketization has transferred public resources to private ownership, weakened public interest regulation, and opened new global labor markets for exploitation. The paper reviews these processes, explores their historical roots taking the electric telegraph as a case study and points to the social and environmental harms they cause. It concludes by asking what implications restoring these issues to a central place in analysis has for public policies towards AI.

Exploring the Impact of AI Systems

On November 30th, 2022, a then relatively unknown artificial intelligence startup, Open AI, launched ChatGPT. Trained on vast troves of data harvested from the public internet, programmed to identify patterns and structures, and employing everyday conversation (chat) in interactions with users, it generated mostly plausible answers to users’ queries, translated between languages, and produced new texts in a variety of forms and genres. Their release marked a watershed moment in efforts to build machines matching human cognitive and creative capacities and possibly surpassing them. Companies developing AI point to its positive applications in medicine and other areas of public benefit.

Emerging systems promise “truly human-centered AI” that can “navigate ordinary homes and look after old people”, provide “a tireless set of extra hands for a surgeon”, or be employed in “training and education.” Critics are unconvinced. Dark warnings of existential threats to social and political order as machines pursue their own agendas jostle with mounting concerns over more immediate impacts on the future of work and employment, surveillance and privacy, and the integrity of public debate and democratic processes.

Marx's Analysis of Relations between Capital, Labor, and Automation

There is a rapidly growing literature in this area. The handful of pages, “The Fragment on Machines”, included in Marx’s notebook, the Grundrisse (groundwork), complied in 1857 in preparation for drafting Capital, are particularly relevant to the argument I want to make here. Current discussions around AI are the latest contributions to long-standing debates on the consequences of mechanizing human skills and knowledge.

Debate begins in earnest in the 1830s with the first factories built to house self-acting machines for cotton manufacture. As Andrew Ure argued in his influential book of 1835, The Philosophy of Manufactures, the factory system shifted production decisively from handcrafted work conducted in domestic dwellings and small workshops to a “vast automaton, composed of various mechanical and intellectual organs, acting in uninterrupted concert (driven by) the moving force” provided by steam power fueled by coal. Ure was an unashamed enthusiast, seeing factories laying the basis for “the most perfect manufacture” dispensing “entirely with manual labor” and relegating workers to caretakers, ensuring the machines operated at maximum capacity.

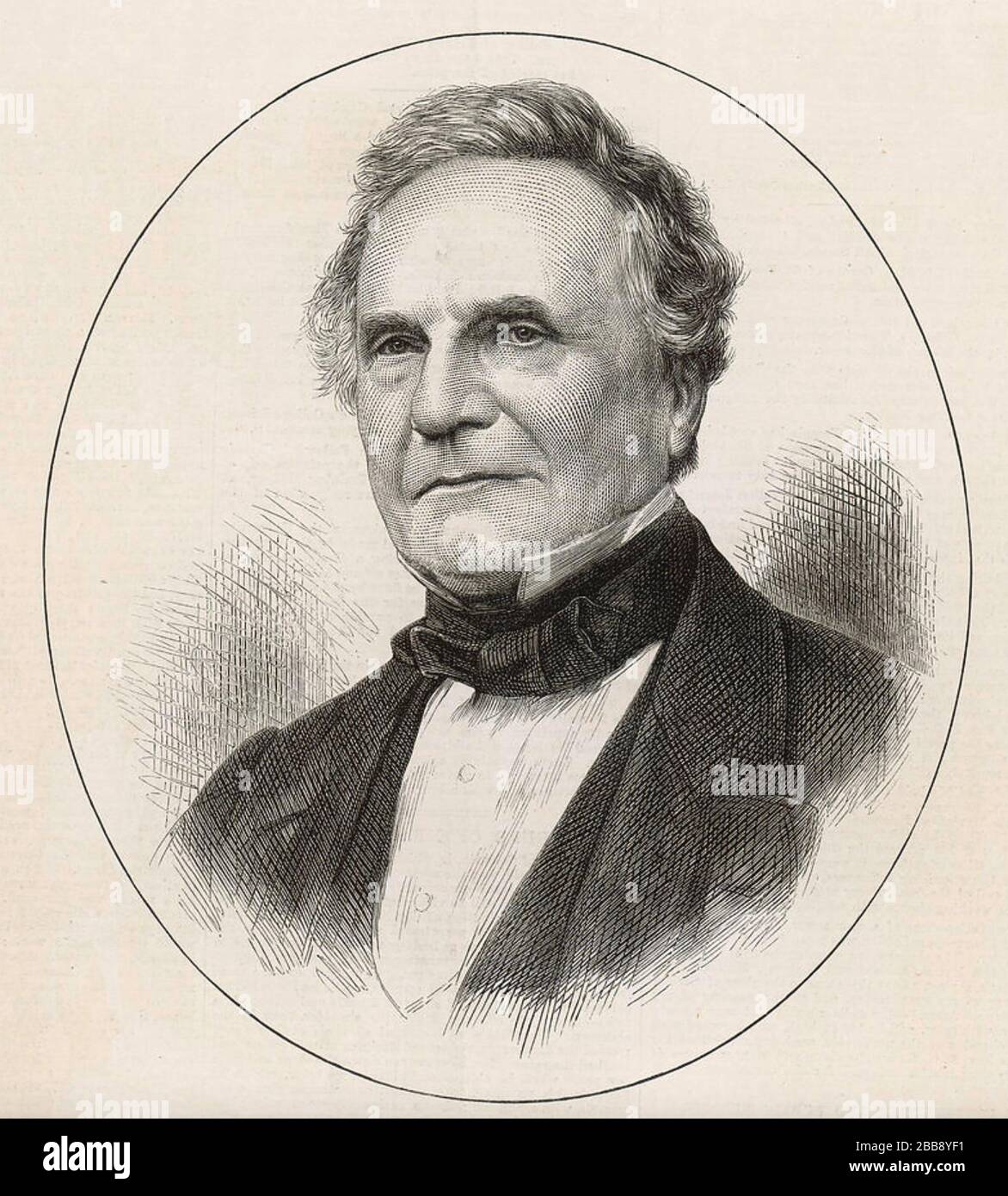

Charles Babbage's Perspective on Mechanisation

An alternative survey of mechanization was provided by Ure’s contemporary, the eminent mathematician, Charles Babbage. His book, On the Economy of Machinery and Manufactures, appeared three years before Ure’s, in 1832. Babbage’s account set out “to trace the causes and consequences of applying machinery to supersede the skill and power of the human arm.” Babbage was better known in his lifetime for efforts to build machines that replicated mental processes. In 1822, he announced his Difference Engine designed to calculate navigational and astronomical tables. Babbage's work gained a wide readership, including Marx, and laid the foundation for further discussions on the economy of machinery and human labor.